What is Platonic irony? When reading Plato’s dialogues philosophers are often keen to highlight irony within his texts. Irony, however, is not necessarily what we think of it today. Rather, Platonic irony is carefully constructed and inserted into the text by Plato himself. Platonic irony is deeply dialectical in the Socratic sense, since Plato’s literary and philosophical irony is generally found in the dialogue partner of Socrates.

While Socrates does not get the upper hand against his opponents in all of the dialogues, and while Socrates is also silent or relatively silent in other dialogues (or altogether absent, like in The Laws), it is generally the case that Plato uses literary irony between the two main dialogue partners. Keeping with Socrates, as he is the most famous of Plato’s dialogue speakers, we know that Socrates is wise, well-informed, and generally the sharpest of the minds within Plato’s works. We expect Socrates to do well as the dialogue unfolds after having been introduced to him. Given Socrates’s high reputation we have to him as readers, but also Socrates’s high reputation in ancient Athens, there is a certain irony that lesser minds (the sophists) constantly get drawn into discussion and debate with him where they are exposed for fools and deviants. (Yet the greatest irony in Plato’s corpus is how Socrates is the one who dies.)

Irony in Plato’s dialogues is something missing in most English readings of Plato, in part, because of the language barrier between English and Greek speakers. Prior to the 20th century, most readers of Plato had to read the Platonic dialogues in Greek. This meant a mastery of the ancient Greek language. While many professional philosophers are forced to retain a reading competency in the primary languages of the authors they deal with, the fact remains most people (including professional philosophers) will read in their primary language meaning that Plato is no longer extensively read in Greek which hampers some degree of the irony contained in his texts.

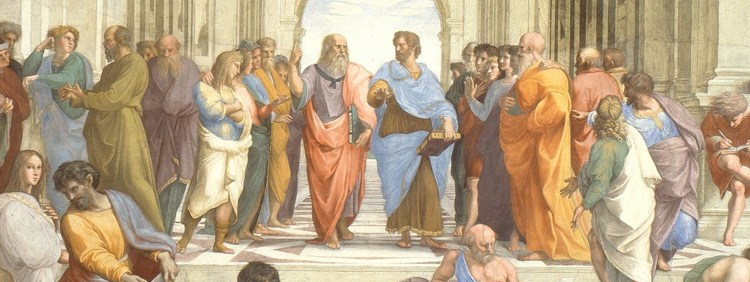

To highlight Platonic irony I will use three examples from the Republic, the most famous and well-known of Plato’s dialogues. Platonic irony is literary, but with philosophical consequences. I examined aspects of Platonic irony already in my published commentary over the political philosophy within Plato’s Republic from an examination of the conversations, imagery, and language used by Plato. It is important to remember that Plato’s dialogues are themselves in the form of a drama—a play, and irony was a rich and steeped tradition in Greek theater.

The first example of irony in Republic is in the character of Thrasymachus. Thrasymachus is one of the more memorable (if not most memorable) of the sophists that Socrates engages in the dialogue, yet he has a small speaking role in comparison to Glaucon and Adeimantus. The name Thrasymachus means fierce or wild man—a savage fighter. The implication being Thrasymachus is a savage beast, a brute, a person who is not really human.

When we first encounter Thrasymachus Plato (through Socrates) describes him as “coiled…up like a wild beast about to spring, and he hurled himself at us as if to tear us to pieces.” The description of Thrasymachus as a predatory animal is meant to convey literary irony given his name and the manner in which he is described and how he acts in the dialogue. He is met as a beast, a brute, a savage.

Furthermore, Thrasymachus’s speech is short and ineloquent. Also reflective of his brutish nature. Lastly, and this should not be a surprise now, Thrasymachus’s thesis on justice that it is in the interest of the stronger is also brutish and savage. Thrasymachus, the animalistic brute that he is, is introduced to us in the dialogue like a predatory animal who pounces and startles Socrates and Polemarchus, he speaks ineloquently (in sharp contrast to the soothing and eloquent speech of Socrates), and his thesis on justice embodies his animalistic nature.

There is a further irony given Thrasymachus’s animalistic and wild nature insofar that he encounters the civilized man—Socrates—and is pacified. We never learn if Thrasymachus really agrees with Socrates on the nature of justice. But Socrates does defend Thrasymachus against Adeimantus, as if he has become his domesticated pet, later in the Republic, “Don’t slander Thraysmachus and me just as we’ve become friends.” How is chaos and disorder brought into order and how is something feral and savage domesticated and made acceptable to be around? Through the logos—rational speech. (This builds on an early indication of literary irony in the Republic when Socrates and Glaucon are stopped by Adeimantus’s slave boy forces them to stop (display of force) and Socrates asks if he could persuade him to let them go if he would—Plato builds up the use of rational persuasion over and against the use of force as an ironic theme in the dialogue.)

Another example of Platonic irony through names is the conversations between Socrates and Glaucon. Glaucon, in Greek, means Owl-eyed. The owl is the wisest of all birds in traditional folklore because owls live long. The longer one lives the wiser one becomes. Athena, the goddess of wisdom, is often imagined as having an owl on her shoulder or nearby to indicate her wisdom. Through the name Glaucon, Glacuon’s name literally invokes the goddess of wisdom and that he should be a wise teacher.

The reality is the opposite. Glaucon is not a wise individual at all. He is worse than Thrasymachus in many ways as he becomes the main dialogue partner with Plato (itself ironic because “wise” people who aren’t really wise are the ones who end up speaking the most—especially on things they do not really know). Glaucon is set up ironically much like Thrasymachus. For those who would have known the Greek language they would have been introduced to Glaucon as a wise character by his name alone. As the dialogue unfolds Glaucon’s positions become less the reflection of wisdom and more the boastful expressions of opinionated ignorance. And yet, Glaucon does show moments of wisdom if he is willing to learn and listen from Socrates.

Famously, as we approach that famous myth of the Cave, Glaucon, who has now begun to attentively listen to Socrates rather than interject against him, recognizes that the people enslaved in the Cave are depicted strangely; something that ought to make thinking individual cast suspicion as he does. Glaucon is on to the fact that the Cave, tyrannical and ignorant as it is, is awfully similar to the world Glaucon is familiar with. Socrates does say in response that the Cave and the people in it “are us.” Glaucon’s moments of wisdom manifest themselves when he actually lives up to his nature (being an owl). The owl is wise because it has not only lived long but because it quietly observes the world before it. Glaucon’s moments of wisdom occur when he listens and observes. Glaucon’s foolishness is on full display when he impetuously engages the wiser Socrates out of fits of passion and rage. Perhaps many people today should take Plato’s ironic message to heart.

A final example of irony is how the sophists believe that they differ in their views of justice but that they are all linked together. For example, the savage thesis of the strong over the weak logically exhausts itself in those in advantageous positions taking advantage of those in insecure positions. This is what Glaucon’s myth of the Ring of Gyges entails. If justice is injustice, as Glaucon argues, it is not that Glaucon disagrees with Thrasymachus but it is that he agrees with Thrasymachus. The difference is that Glaucon takes the next logical step in following Thrasymachus’s principle. The logic of the sophists rejecting any knowable truth and relativistic notion of justice leads to tyranny and ignorance—which is what the Cave embodies first and foremost.

Irony is a major literary and philosophical theme through Plato’s many dialogues. They are also deeply important to recognize when reading Plato so as to understand the arguments of Plato’s. Without a recognition of Platonic irony one reads Plato without really reading Plato.

________________________________________________________________

Hesiod, Paul Krause in real life, is the editor of VoegelinView and a writer on art, culture, literature, politics, and religion for numerous journals, magazines, and newspapers. He is the author of The Odyssey of Love and the Politics of Plato, and a contributor to the College Lecture Today and the forthcoming book Diseases, Disasters, and Political Theory. He holds master’s degrees in philosophy and theology (biblical & religious studies) from the University of Buckingham and Yale, and a bachelor’s degree in economics, history, and philosophy from Baldwin Wallace University.

________________________________________________________________

Support Wisdom: https://paypal.me/PJKrause?locale.x=en_US

My Book on Plato: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08BQLMVH2

Brilliant review and analysis. Thank you for your efforts to bring big philosophers like Plato to the light in the blogosphere. Will reblog it!

LikeLike