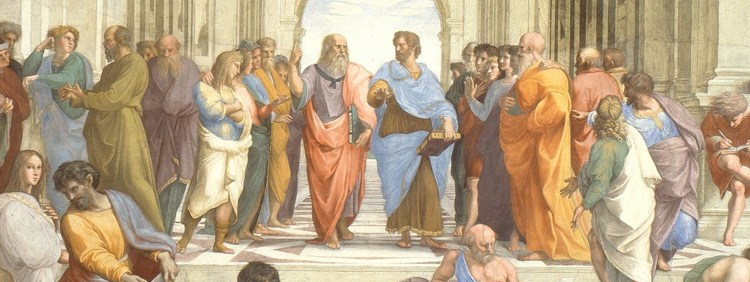

The history of political philosophy is often divided between the classics (or ancients) in contradistinction to the moderns. Political philosophy, from the time of Socrates and Plato, has always been regarded as the queen of the philosophical enterprises because it most pertains to the question of being human. Hence, political philosophy is necessarily tied to anthropology, and more specifically, ontology. But what is the great divide between ancients and moderns?

This dichotomy does have its shortcomings insofar that there were ancient philosophers who disagreed with this view (especially Epicurus and the Epicureans) and there were modern philosophers who challenged the post-Baconian consensus (but these figures were more-or-less inheritors of the ancient tradition of political philosophy). The great divide comes from the fact that ancient philosophers regarded humans as social animals. Hence, the political was innately social and sought to foster bonds of relationships which would give meaning and fulfillment to human life. Modern political philosophy, especially as found in Bacon, Hobbes, Locke, and Spinoza, but especially Hobbes and Locke, is that humans are a-social consumers. In other words, humans are independent of each other and would want to be independent of each other. Humanity’s fulfillment comes in man’s separation from man, whereby man came peacefully live a consumeristic life without fear of violent death from others.

The divide in this question concerning man leads to the construction of political systems which embody the first principles of these competing anthropologies. Namely, classical political thought sees political life as social, something without boundaries that prevent people from associating with each other. Classical political thought strongly promotes the idea of civil society and civic virtue where humans live out their social lives with others and for others.

*

Classical political philosophy divided between Greco-Roman and Christian conceptions of the political. The Greek model of classical political thought, bequeathed by the likes of Plato and Aristotle, saw knowledge practically applied to one’s life and vocation, as the bond that tied people together in the polis. Hence, for the Greeks, the question of political philosophy and the resulting virtue needed in political life is also an epistemic question. Roman political thought, bequeathed by the like of Cato and Cicero, was based on patriotism – love of fatherland: patrie. One’s land, where one’s home and way of life was situated, where one’s ancestors had worked and died to build said home, is what tied people together in the polis. In both cases, however, we see the bonds of the social animus bringing people together through various ways and means.

Christianity did not reject the Greek and Roman conceptions. Anyone with a familiarity with Christian political thought or the Catholic Catechism knows Christian political philosophy – inheriting the Greek and Roman traditions – concurred that practical wisdom leading to virtue (phronesis) and patriotism are good things that help bring society together. What Christianity added was its theology of eros, or of love, to the political dynamic. Love, Christianity claimed, was the needed glue to actually manifest the Greek and Roman project to its fulfillment. It’s not enough to simply live in a land for the land to bind one together with others. One must love the land they live in and grow attached to it. Likewise, one must love the pursuit of wisdom – seeking after truth itself (which Christianity argued is the essence of the good life since God is truth so seeking after truth is the restless search for God). Only through love of wisdom and then applying that to life will one excel in their vocation and bring order and excellence to the city. Moreover, however, one must actually love their neighbor and give their energies to their neighbor. The love of fatherland is quite a fruitless endeavor in solitude. Just as is mastering one’s vocation is a fruitless endeavor in solitude. One ought to love their homeland as an expression of not merely the love of ancestors, but also an expression of loving those who are also in the land with you at present. Love is the great relational bond that brings the Greek and Roman projects to their fulfillment. Love, of course, is social – it is, by definition, relational.

The argument from the classical political philosophers was that humans would, when not forced by external powers, naturally engage with each other in a constructive endeavor of building what we call society. It might be messy, it might have episodes of violence, but humans aren’t will bond with one another through various means. Furthermore, this endeavor was the great story: the story of building, of finding, a place to call home. This is evidenced by the ancient poets and epics (Hesiod, Homer, Virgil, the Biblical authors) on top of the classical political philosophers (most explicitly Aristotle, Cicero, and St. Augustine).

*

The modern political project begun in the so-called Enlightenment had a different picture of humanity than the ancient anthropologies of either the Greeks, Romans, or Christians. Instead, man was essentially a consumeristic and hedonistic body in motion. Furthermore, man was a-social in his very nature. Man’s sociality was only because he wished to escape the brutal living in the state of nature.

Modern political philosophy posits the independent self. Not only is the self independent of other humans, the self is, properly, independent of nature. That is, nature exists for our consumption and nature does not provide any meaning to our existence because natural beauty doesn’t exist. This is an epistemic outcome of the epistemological doctrine of the tabula rasa. There are no innate ideas and no intrinsic preferences and values. Everything is, properly, neutral and we merely proscribe value onto things based on sensation. The good is something that is stimulating to the senses. The beautiful is something that is stimulating to the senses, etc. The bad is something that brings pain to the senses. The ugly is something that causes, for instance, sight, to turn away, etc.

The problem of life in the state of nature is that man is not independent enough. By not being independent enough he is, paradoxically, not really free in the state of nature. Though Hobbes and Locke (and Spinoza) characterize man qua man (e.g. self qua self) as absolutely free in the state of nature, the problem is that other people exist in the state of nature. Because others exist in the state of nature our drive for consumption leads to competition and the state of nature is either de facto a state of misery and war (Hobbes) or descends into a state of misery and war (Locke). The result is that to really achieve independence, that is, separation, we must construct barriers or regulatory bodies that restrict unimpeded movement in order to actualize freedom.

A new paradox emerges (at best) or an outright contradiction follows from this modern political project. The modern notion of liberty is unimpeded movement or access or power to do. Bacon, Hobbes, Locke, Spinoza, and even Rousseau, all agree to this. The problem is (sans Rousseau for having the view that mankind is naturally benign) that without any restrictions we negate freedom in the state of nature through endless competition and collision. Hence, man is independent if he is alone. The task of modern political philosophy is what political theorists call “political hedonism,” which is the creation of systems and “societies” where pleasurable consumption becomes the highest value (or good) in life. To achieve this force must be employed to separate humans from other humans because human contact and interaction with each other usually leads to physical harm and problems. Anyone who has read Hobbes, Locke, and Spinoza already knows this.

Furthermore, since man is a body of mass in motion, following the laws of physics of the new science, all there really is in the modern political project is force. Thus, in order to achieve man’s independent existence from others, wherein he will be truly free, force is what achieves this goal. Forced separation from others, forced regulation from the leviathan or commonwealth legislature, and forced directives in how to interact with others should interaction be unavoidable, is what the modern liberal political project entails.

As most critics of the modern political project have noted, what modern political philosophy aims at achieving is the complete depersonalization of society. In other words, the homogenization of society is what must be achieved for sameness results in no conflict. People are depersonalized through law, the market, and the state (insofar that a person can be seen as just a utilitarian tool for the state’s empowerment and existence rather than as an image of God as per Christian anthropology or fellow citizen and friend as in Greek and Roman political philosophy). Humans end up seeing others as mere consumers.

*

Thus, the great divide in political philosophy has, so far, come down to these competition anthropologies. Are humans social creatures moved by “irrational” (according to modern prejudices) forces such as particular loves (which is discriminatory by definition) and tending toward communitarianism where one finds fulfillment by coming into a culture, community, history, story, and shared experience? Or are humans a-social consumers moved by the only rational force there is: the want for bodily pleasure through consumption where one finds fulfillment by being liberated from the constrains of social norms and mores, cultural ties, community, and shared stories and experiences which bear down on the self-making self? One sees the conundrum the concept of the political faces.

Liberty, in the classical context, meant ontological flourishing. Liber, in Latin, meaning the “free one,” is etymologically rooted to the Roman god Liber – who is the god of fertility. Hence, flourishing. Human flourishing, since humans are social animals, is achieved through some degree of being part of a social enterprise. After all, the very word “society” has the root cognate social in it. To be free was either to control one’s desires in favor of the rational intellectual pursuits (per Aristotelianism and Stoicism and classical Platonism) and thus bring about the harmony and self-mastery of one’s ontological state, or to orient and direct one’s desires to the permanent things that the rational soul seeks (per Neoplatonism and Christianity).

Liberty, in the modern context, is all about power: the power to do something without repercussion or barrier to doing. The primary end of this power is to consume so as to satisfy, but doesn’t desire only ever get more desire? Hence why the classical anthropologies entail either the control of the desires or the direction of the desires to the things that will satiate it (e.g. God, the transcendent, the good, true, and beautiful, etc.). We must also ask: if we agree with the social anthropological position, what really does bring humans together in community? Is it knowledge translated into practical and virtuous living in? Is it the land we call home and tend to? Is it love of wisdom and love of land and our neighbors? Or something else entirely?

________________________________________________________________

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView. He is writer, classicist, and historian. He has written on the arts, culture, classics, literature, philosophy, religion, and history for numerous journals, magazines, and newspapers. He is the author of Finding Arcadia, The Odyssey of Love and the Politics of Plato, and a contributor to the College Lecture Today and Making Sense of Diseases and Disasters. He holds master’s degrees in philosophy and religious studies (biblical studies & theology) from the University of Buckingham and Yale, and a bachelor’s degree in economics, history, and philosophy from Baldwin Wallace University.

________________________________________________________________

Support Wisdom: https://paypal.me/PJKrause?locale.x=en_US

Venmo Support: https://www.venmo.com/u/Paul-Krause-48

My Book on Literature: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1725297396

My Book on Plato: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08BQLMVH2

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/paul_jkrause/ (@paul_jkrause)

Twitter: https://twitter.com/paul_jkrause (@paul_jkrause)